Linguistics and Fantasy

Posted by Meg

World-building is a complex process. It is a chance to draw from history of our world and combine it with something unknown. But it is also a struggle to create something fresh yet familiar. To draw upon what is loved about the fantasy genre and to mark your own territory. I think most fans can agree that it’s one of the most fascinating aspects of fantasy.

Peat received an interesting email from a fan (Becca, a linguistics major!) questioning his approach to creating the languages and cultures that appear in The Warded Man and The Desert Spear. Here’s what he had to say:

Hi Mr. Brett,

Becca Gimlett here, linguistics student from California now studying abroad in Berlin, long-time fantasy fan, occasional creeper of your blog, admirer of the contents of your bookshelves. I also enjoyed The Warded Man and The Desert Spear and perhaps stayed up slightly too late on weekdays devouring them, but you’ve probably gotten plenty of those emails before now. You’re also busy, so I’ll leave the praise implied and skip to getting to my question. (No hurt feelings on my part if you’re too snowed to answer. I’ll just go bug Sanderson instead. Kidding, just kidding…)

As you’re probably aware, there’s an unfortunate multitude of people in this world who look down upon or even doubt fantasy as a form of literature, and these sorts tend to congregate in the Humanities departments of colleges and universities. I encounter them all the time, or perhaps they encounter me. Before I began studying linguistics, however, it was easy enough to defend (the potential of) the genre as a form of artistic expression. Ever since that first introductory class, though, it’s become harder to do. I’m sure the fantasy fans who decided to study geology, physics, biology, whatever might have similar problems. While my respect for Professor Tolkien has multiplied, my ability just to enjoy a fantasy book has gone down hill, because that made-up language or that name or that casual statement about consonants that I swallowed beforehand without thinking is now a glaring rip in the patchwork.

Thankfully, the recent trend in fantasy lit nowadays has been for authors to do their research, and the days of blind copy-catting are (crossed fingers!) over. No more languages that look like keyboard smash, no more random mountains, general common sense switched on.

The short version is that your books fell into the “nowadays” category for me when I read them a couple months ago, but in a rather unusual sort of way. Not the “slip past the radar” way but “hey, maybe this Brett dude went through the trouble not just to avoid errors but to actually…get things right?” one. And so, to arrive at long last to my question (apologies for the long-winded lead-up), what sort of research did you do into building the language of the Krasians? Obviously it has some real-world inspirations, but also so deviations, and I’d be interested to know what you decided to change/keep/leave out and why… And, because this is my area of interest (we’re talking, would-do-dissertation-on-the-topic type of interest), what sort of thought went into the naming systems for both cultures? I ask because I don’t know if I should let myself have an all-out linguistics-nerd-out on what you created, or just not question it and plow onward when Daylight War hits the market 🙂 No worries at all if I should just do the latter.

Many thanks for writing some killer fast-paced didn’t-make-me-want-to-mourn-the-future-of-fantasy books. They were my first Kindle reads and will always have a place in my heart. I look forward to a response but understand if that’s not possible. Also, thanks for reading this email!

Tschüss, as the Germans say!

Becca Gimlett

And Peat’s response:

Hi Becca,

Thank you for writing and all the kind words.

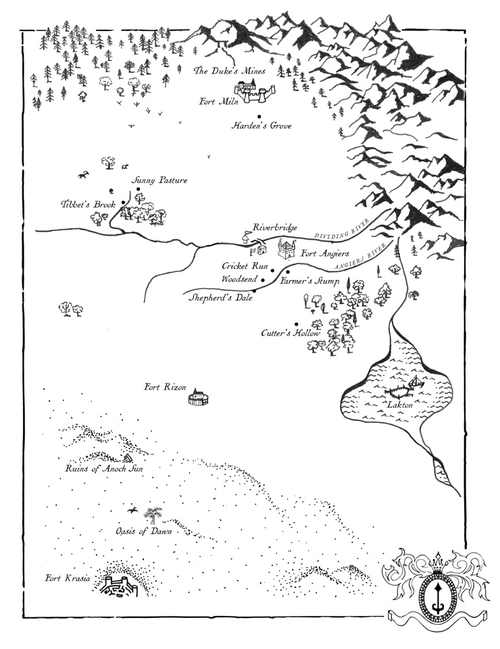

To answer your question, I am not a linguistics expert, but having worked as an editor for years and studied Latin and French, I have a fairly good sense of how language is put together. I try not to overwhelm readers with too many Krasian words, but I have been careful to be consistent in structure with the words I use, showing common roots in the things that are important to Krasian culture. While some effort was made to give the language a Middle Eastern flavor, it is for the most part fabricated.

The Thesan naming system is essentially to use ‘normal’ western names, but alter the spelling, usually to simplify. This was meant to represent the loss of literacy after the Return, when demons burned the libraries. I was inspired in this by Middle English, where the same word can be spelled three different was on the same page.

Thanks again.

Regards,

Peat